The concept of “masking” is a bit of a cause in neurodivergent quarters at the moment. It’s particularly front-and-centre in feeling our way to defining a female autistic identity as distinct from the dominant stereotype of the extreme male brain [Baron-Cohen 1985]. I’m a bit sad to note that, once again, I can’t see myself here particularly clearly. I mean, I’m supposed to have “found my tribe” and to a certain extent that’s true – with autistic people who’re also lefty, queer-positive, (pro)feminist, and trans-positive I’m unusually feeling much more relaxed and ‘at-home’ than with their NT counterparts. However, way that autistic identity and female ‘masking’ in particular is being formulated seems to me to be too often a-historical, individualising, insufficiently critical of gender stereotyping and, despite growing evidence that a majority of autistic people are also queer (as well as slowly improving diagnosis of black and brown autistic people) intersectionality often also seems minimally addressed. Although damaging forced practices aimed at normalising autistic people such as ABA are frowned on in the UK, nevertheless there is a self-actualising tone and underlying assumption that it is the key aspiration of every autistic person to appear as ‘normal’ as possible within the neoliberal order that structures much of the discourse about autism. This is facilitated by the psychological terms within which autism is generally modelled. To me, autism needs to be situated in a more complex and historicised model of social identity.

‘Theory of mind’ [Baron-Cohen 1985] – the notion that autistic people are unable to imagine the mental processes of someone else, or even themselves – still stalks the terrain, though now largely discredited. Concepts such as ‘alexithymia’ [inability to understand your own emotions] or ‘alexipersona’ [inability to form an identity] persist. There’s much verbiage on the internet deriving from this model of autism – this article summarises it pretty well:

An autistic teenager may create one false persona after another, as explained by an autistic teenager: “I don’t have a personality; I mimic people”. They become a chameleon, as in the quotation, “My personality changes a lot around different people”. The sense of self is contextual. The construction of personality is from the fragments of the people with whom they want to create a connection and acceptance. [Self Identity & Autism https://www.attwoodandgarnettevents.com/blogs/news/self-identity-and-autism]

The general idea, often described by autistic people themselves, is that autistic people find it hard to interpret their own emotions, hence lack self-awareness and are therefore unable to develop a stable social identity. Whilst this description may well match the everyday experiences of autistic people, and is at least partly drawn from accounts by autistic people themselves, it represents not only a misinterpretation of autistic experience but also an individualising construct of identity itself. Autism is usually placed in the context of psychology, cognitive science, or neurology which have particular constructs of identity. Probably the one most informing the idea that autistic people can’t ‘do’ identity is that identity is based in a continuity of memory, experience, and psychological characteristics observed over time. Autistic people often have difficulty in interpreting emotion and experience into language and this has led to a widespread assumption that autistic people lack the ‘tools’ to construct an ‘identity’. To me, what they are describing here is ‘personality’ and not ‘identity’ which, to me – an alumna of the school of cultural materialism – is not interchangeable with identity. Identity, as understood in a Foucauldian discourse model, is formed through a constantly evolving and multi-faceted set of narratives:

Of particular interest is Foucault’s assertion that our identities are not fixed in a traditional sense but mediated by the many rich, dialogical discourses we encounter each day. This identity scheme is suggested in much of Foucault’s philosophy, particularly in Discipline and Punish and The History of Sexuality [Urbanski, 2011]

In other words, identity is a set of narratives describing social positions and categories, whilst personality is the way we might summarise ourselves to someone we’ve recently met and are forming an emotional bond with. Memories, emotions and experiences we feel have ‘formed’ us and which we need our nearest and dearest to understand when they respond to us. To me, this is an area where autistic people might reasonably be said to struggle to make themselves understood. It’s not that we don’t know where we’ve been and how it made us feel, it’s that it doesn’t readily form itself into a coherent narrative. It’s also not really an area of much focus for many autistic people. I have a tendency to experience pretty much every emotion as stress and generally find emotions just an unwelcome intrusions to the airy reason I prefer to espouse. I dislike irrationality, it’s unpredictable and scary. I have a tendency to narrate my personality to others in terms of the clinical features of autism. Because trying to communicate my actual feelings and experiences will cause most neurotypical people to deny the validity of my experience as it’s outside of their own. Reality checking queries such as “you know when that thing happens and you feel x” is often met with neurotypical people accusing you of misrepresenting your own experience or some even more judgmental way of communicating to you that you are weird – and not in a good way. After a while, you stop trying to communicate your experiences unless it’s backed up by cognitive science. Autistic people tend to suffer from a dearth of appropriate reality checking rather than an inability to parse reality. The relief of being able to say to another autistic person “you know that thing . . . ” and have them say “ooooh yes! I know what you mean” is transformative. Other autistic people usually seem to have little trouble interpreting my emotional states from my behaviour. When I first knew other autistic people I frequently had revelatory moments along the lines of “Oh! that must be how it looks when I behave like that”. We lack accurate mirroring which is a key function in forming understanding of our own behaviour and emotions – in forming a sense of self through an ability to model how others see us which we can finally match to how it feels on the inside.

Discussions of identity in autistic discourses tend to revolve around the concept of ‘masking’ or ‘camouflaging’. This is a vague and anecdotal set of narratives about how autistic people, particularly women, go about the process of trying to function effectively in [neurotypical] social environments. At the moment it’s also functioning as explaining why so few women are diagnosed (it’s our fault, we’re hiding) and why we struggle to form identities of our own. The idea of what ‘identity’ is seems entirely drawn from psychology but is rarely defined in anecdotal accounts so its valence wanders around. The general gist seems to be that girls are (a) more anxious to please and (b) quieter and more introverted than men. It doesn’t seem to have occurred to anyone that this is an extremely traditional stereotype of femininity. So being anxious to please and self-effacing, naturally autistic women (a) can ‘pass’ more easily just by keeping quiet and (b) will squeeze every ounce of their being into an effort at “agreeableness”. Well, honestly, welcome to the 1950s. Pass me the instant cake-mix!

On the whole, the anecdotal accounts of female masking that I’ve read don’t match up with my own experience – fair enough, this may be partly to do with auDHD as opposed to autism in that I can’t easily retire into quiet ‘feminine’ self-effacement as a masking strategy. But this in itself highlights a gender stereotypical tendency in the discourse which painstakingly points out that each autistic women’s experience is unique then paints us all as stereotypically feminine. I’m sure I’ll be corrected but I think auDHD is nigh impossible to suppress or conceal and is floridly at odds with anyone’s notion of ‘femininity’ – including that of the prevailing feminist tendency which has been inclined to view female identity in terms which often get (easily) confused with radical feminism but which owe more to cultural feminism as defined by Echols [1983]. Feminism is more likely to be expressed as a celebration of an imagined feminine essence distinct from masculinity. Through the 90s, cultural feminism moved away from a disappointing radical confrontation with patriarchal capitalism and a relatively deconstructive attitude towards gender stereotypes towards a more liberal programme of reclaiming ‘femininity’ as a positive force in the world. The two seem to have merged in the currently most visible form of ‘gender-critical’ feminism which slides ever rightwards celebrating what amounts to a fairly traditional notion of an essential feminine identity and sprouting what’s been described as ‘post-fascist’ femosphere [Kay, 2024]. However, I’m not here to get into the weeds of feminist theory except insofar as it impacts efforts to construct a model of female autism.

So how does gender appear in discourses of autism? Numerous studies have demostrated that autistic people are far more likely to identify as queer or gender-non-conforming:

“These findings provide some evidence that social norms (which change across time) may have affected individuals’ acceptance of their specific sexual orientation; yet, our results support overall that autistic individuals […] are more likely than others to identify with diverse sexual orientations and less likely to identify as heterosexual—which may be affected by social norms, biological differences, other factors, or a combination of these.” [Weir et al, 2021]

As the medical profession has finally begun to diagnose non-white-straight-cis-men as autistic, the ‘extreme male brain’ theory has also been discredited, moving towards more complex models of autism. Again, my purpose here is not to get into the weeds of schools of thought in defining autism but to look at how autism institutions are defining autistic femininity and at how this overdetermines discussion of female autistic ‘masking’ strategies.

The National Autistic Society summarises autistic reports of masking without gender distinctions:

hyper-vigilance for and constant adaptation to the preferences and expectations (whether expressed, implied or anticipated) of the people around you tightly controlling and adjusting how you express yourself (including your needs, preferences, opinions, interests, personality, mannerisms and appearance) based on the real or anticipated reactions of others, both in the moment and over time [https://www.autism.org.uk/advice-and-guidance/topics/behaviour/masking]

The UCLA Health blog refers to young females:

Young females typically are more motivated than males to fit in and be social. Females with autism learn or mimic socially acceptable behavior by watching television shows, movies and the people around them. They may copy the facial expressions of others to hide social communication challenges. Those efforts can cause mental exhaustion, stress and anxiety.” [https://www.uclahealth.org/news/article/understanding-undiagnosed-autism-adult-females]

It does seem to me that a hyper-vigilant focus on how one appears to those around you is a characteristic feature of teenaged years. The psychological model hopes that young people will form a stable personality during these crucial teenaged years as the brain undergoes significant biological changes. The assumption here is that this hyperfixation on trying to avoid ‘otherness’ doesn’t change at all as the subject ages. I do recall as a teenager studying the behaviour of ‘normal’ girls and trying to replicate it – with a disastrous lack of success I might add. Obviously, I grew up and searched instead for environments where my ‘lack of fit’ might be less ostentatious.

The UCLA blog goes on to list differences between young autistic women and men – young women apparently have fewer social difficulties, internalise their symptoms resulting in higher rates of anxiety, and to match their ‘special interests’ to ‘feminine’ topics. By this reckoning, I’m a man. This resonates uncomfortably with how my gay identity works. Once again. Mannish, butch, thinks like a man, too analytical, detached, dominant in groups. Yep, I’m a man apparently. Well, I’m gay. But am I trans? Nope. Less than no interest in my body apart from keeping it in working order, couldn’t give a flying fuck which gender I am, find the whole business of biologically sexed bodies distasteful and would rather avoid thinking about it as much as possible. Transitioning involves thinking about it rather a lot and is hence entirely bye-the-bye for me personally. (Hasten to add I unreservedly support all trans people’s right to self determination and full medical support, but it’s for me to decide whether I personally am a man’s mind in a woman’s body or not.) I’m a detached and analytical cis woman who likes sci-fi, shoot-em-up computer games, rapid bpm – and I’m loud and I fidget incessantly – get over it for heaven’s sake!

Again, I’m taking aside the topic of whether failures in diagnosing girls is due to girls presenting differently in which case the ‘problem’ is internal to girls and not, of course, due to the prejudices of what has been a male dominated medical profession. The diagnostic criteria need tweaking a bit and then everything will be fine. God forbid the problem could be within gendered structures of power and not just attributable to girls being naturally quiet and inoffensive.

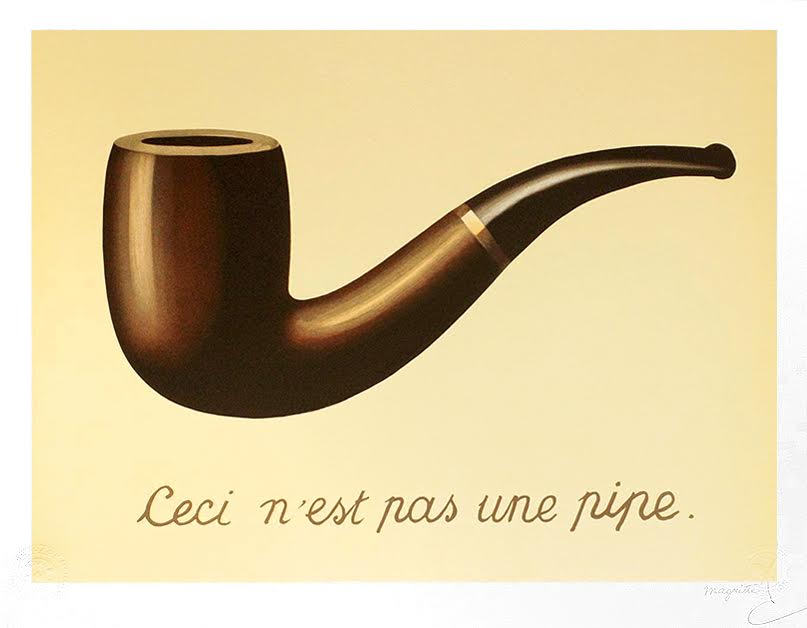

Am I saying that I don’t mask? Certainly not! Of course I mask, there’s rent to be paid and contrary to popular opinion about autistic women I have pretty serious social difficulties and a bunch of cognitive issues. I did make an effort to mask at school for the purposes of avoiding bullying as far as possible – mostly unsuccessfully. What I don’t remember is “tightly controlling and adjusting how you express yourself (including your needs, preferences, opinions, interests, personality, mannerisms and appearance) based on the real or anticipated reactions of others, both in the moment and over time” [NAS ibid]. Clearly I lack the focus to pull off anything that coherent. My approach was rather more purely mimetic – I observed in a detached sort of way and attempted to reproduce the markers of the symbolic order of whatever present company I found myself in, if I think of a pithy summary it’s Isherwood’s “I am a camera”. To this extent, many autistic women’s accounts of masking do resonate with me. Again and again, autistic women themselves refer to mimetic efforts to fit in. This anonymous contributor to the r/AutismInWomen sub-Reddit seems to sum up the prevailing sentiment on identity confusion due to masking for autistic women:

“I’ve spent most of my life copying the behavior of others because I learned it helped me fit in better and go unnoticed. But this has left me feeling like I don’t have a stable identity of my own. It’s frightening and frustrating because I’m often unsure who I really am, what’s truly “me,” and what’s just something I’ve adopted to feel “right” in social situations”.

She goes on to describe what looks like echolalia – a very familiar aspect of autism for me. It’s an unconscious tendency to mimic others unintentionally. I pick up accents and figures of speech that I find appealing which I repeat pleasurably and often then add to my already idiosyncratic use of verbal language. This is one level of ‘masking’ for me – and it’s the level which I’d describe as largely automatic – as echolalic. The other level is studiously observing how the identity of any particular sub-culture or social grouping is constructed symbolically so as to deploy its markers and recycle its memes as accurately as possible – and hope to get away with it. This is entirely conscious, studied, and within my control. This approach to masking is entirely externalised – shallow and fake – and rarely saves me from “uncanny valley”. But on the other hand, I’ve personally never felt any confusion about ‘who I am’, and from childhood I’ve regarded social identities as based in faintly alarming animalistic ‘pack’ behaviours. At best bafflingly alien and at worst holding a constant threat of bullying discipline of discursive boundaries. I did feel angst at not fitting in but assumed comfortingly that if I could escape to a city I’d find others like me. As I grew up I began to regard a socially acceptable projection of identity more as just a necessary chore if one wishes to be solvent. However, you live and learn and find out that ‘fitting in’ socially is a much more complex and interactive process which brings me to the concept of “participatory sense making” [2013 De Jaegher]. This posits a collaborative approach to ‘making sense’ to each other. I’ll try to elucidate a fairly abstruse construct with a personal anecdote:

I once naively asked a neurotypical friend if neurotypicals have some kind of warning alarm in their heads to tell them they were treading on toes because I never have a clue that I’m annoying someone until they are very visibly disgruntled and hostile. Or boring them until they are visibly glazed – and even then I still don’t know how to fix it. My NT friend fell about laughing and said that of course they didn’t. He said what they actually do is test out communicative strategies and closely monitor the response, if it seems slightly negative they move away from the topic and if it seems positive they might test the boundary a little more, and so on. This was a radical enlightenment to me. Woah, you think about how the other person is responding? You’re not totally fixated on formulating what you literally and exactly mean whilst worrying that you look like an idiotic naive nerd? Thought I’d try it – but no. It’s a bit like pissing and chewing gum to me – I can’t think about what I’m saying and still closely observe the other person at the same time. Well, assuming I can make any sense out of micro-expressions anyway. Someone’s face needs to be doing something fairly elastic before I’m going to notice. And that’s just with an individual. With a group, there’ll be smoke coming out of my as I try helplessly to follow the prime directive of self-awareness but instead start to combust with panic overwhelmed by way too much sensory information incoming much too fast.

So, according to theory of mind models, in order to interact with others in a way which develops and internalises a sense of identity, autistic people are going to come up short. This deficit model of autism sees autistic traits such as alexithymia as errors in need of correction:

“Autistic people are thought to have difficulties with identifying and understanding their own emotions. This is referred to as emotional self-awareness. It is important to study emotional self-awareness as people who are more able to understand their own emotions, whether they are autistic or not, are more able to respond to them appropriately, as well as to identify them in other people.” [Huggins et al 2020]

I know I’m not alone in only being able to figure out what happened in social situations well after the event whilst happily stimming on my own sofa. It’s just real time that stumps me. I also so really struggle to name what I’m feeling, I think this is a lot to do with the fact that there’s always too much going on for me – too much sensory input, too much multi-layered meaning etc. I tend to experience all emotion as anxiety and I have to use trained meditation methods to get a more fine-grained sense of what I’m feeling. I can’t identify emotions at micro level but I can figure out from exploring physical phenomena broadly what emotions are related to them. I also use textual close-reading methods I learned in academia to interpret what people are ‘really’ trying to say – so I’m not opposed to self-help, I just don’t think it’s the whole story. I think we should also be questioning why we feel obliged to struggle to fake these already constructed social identities? In most cases the answer is fairly simple – to avoid bullying and to have some sort of sense of belonging. Less often people reference being able to earn a living but, as an adult, this is my primary motivation, that is, as an adult masking is primarily driven by economic exigency. In other words, NT insistence that we field a readable identity is, in itself, a form of oppression. I’m happy to inform people that I’m autistic and to identify publically as such but I really don’t want to be put to the trouble of representing it coherently! Any more than I want to be put to the trouble of coherently representing a gender. This doesn’t mean I don’t want to be responsible for my end of social interactions but that all parties to the interaction are equally responsible for managing difficulties in empathising with someone who’s subjective experience is not available to your understanding [see Milton 2012 for exposition of the double empathy problem].

To expand on autistic identity confusion, another anecdote illustrates that this confusion is not mine but rather seems to exist in the minds of neurotypical friends, collegues, and acquaintances. Old acquaintances who haven’t seen me for a couple of years frequently remark with some chagrin that I’ve “completely changed”. This always baffled me as I really haven’t. Still autistic, still queer, still a woman etc. Still wince at chaotic dishwasher stacking and melt down from sensory overload in airports. So what on earth do they mean? Again, I applied to neurotypical friend for elucidation – apparently my social identity changes every couple of years. Ah. Yes, indeed, I do burn out with careers and their external regimes of identity, I drop them unceremoniously and then rejig for current job/girlfriend/general-survival-strategy. Identities are basically clothes and memes for me, I drop them as casually as old socks that I can’t be bothered to darn – and these days I really do the cynical bare minimum alignment with any incoming symbolic order. Why do I have all this weird shit no respectable culturati should have in their music collection? Because I like listening to it more than I care what you think, of course! Perhaps neurotypical social identities are a ‘poor fit’ for me because I’m not neurotypical. Because neurotypical people just don’t want to listen to my experience or validate it. Autistic identity should not be constrained by what neurotypical people find credible as an experience. It should be articulated through our own experience of the world and our own ways of processing it.

It’s hardly surprising that my academic research focused on subcultural identity – I wanted to get to the bottom of what on earth identity actually was. At the time, I was getting disappointed with a particular iteration of feminism (according to which I was unacceptably masculine in my thinking – apparently this is largely because I speak authoritatively with analytical detachment, but WTF do you want me to do about my neurology?). I was also jaded with the culture of academia which had been a dreaming spire in my head but an alienating bastion of institutional and cultural conformity on the ground. So I learned that identity is not one thing – I’m not talking about due attention to intersectionality which goes without saying. I’m not going to recap a couple of library sections either but, basically, in cultural theory, identity is a position from which to speak and from which your speech will be inflected (the most crudely obvious example being who can say the ‘n’ word, who can’t, and in what contexts) and which can be indicated by biological, economic, and cultural markers such as sex and complexion on the one hand and cultural markers such as ‘ethnic’ or class background, career, or pink hair and a safety pin through your eyebrow on the other. In these terms, autistic – or rather neurodivergent – identity can be seen as a counter-identity, contesting exclusion from authoritative discourse by re-asserting a despised set of characteristics as a positive identity. Or to put it in a more user-friendly way, identity is all about socially accepted narratives – a short-hand way of categorising people so you know how to ‘address’ them (are you going to treat them as fellows, patronise them, spit at them etc). If society despises you, you form your own social domain with like-minded people and assert a ‘counter-identity’. This is what neuro-diversity and neurodivergent identity is all about. People might still spit at you but you can proudly spit back with a minoritised community in your corner.

A Foucauldian model of subjectivity anchors identity in historical narratives, however unreliable such narratives may ultimately be. Autism has been a neurological type though rather than a cultural identity. As such, it is rarely placed in a historical context beyond a brief history of the development of the diagnosis. It is rarely treated as an historical phenomenon even though it is barely 40 years old – that is, it is not a ‘timeless’ way of being. Whilst there is a debate raging as to why autism diagnosis stats are rising rapidly, this is also rarely treated historically. On the right it’s treated conspiratorially and repressively whilst on the progressive side it tends to be treated as a phenomenon of improved diagnostic processes. The increased diagnosis of autistic women is treated the same way, as correcting a failure of diagnostic criteria. Whilst this is no doubt true, it rather abstracts autism from history and cultural discourse. Given that autism is increasingly seen as at least a partially heritable neurotype it’s unlikely that its incidence in biology is actually increasing but it’s never questioned why diagnostic criteria are improving other than a vague notion of the workings of ‘progress’.

However, if we situate autism in the material world, as Foucault has previously done with madness, this question does rather present itself. Why is autism now? Not millennia ago but now. Why is an articulation of masking so central to the development of autism as a counter-identity? Could it be that material conditions are actually producing autism and an imperative to mask rather than following in the rear to define it? But wait, isn’t it neurological – thus in evolutionary time? How could history be producing it?

In philosophy of mind, autism is beginning to be explored in terms of embodied theories of consciousness, which derive from Heidegger and from Merleau Ponty’s critiques of phenomenological idealism, and which ground subjectivity and identity in the world – as fundamentally embodied. That is it rejects the mind/body dichotomy which still effectively dominates cognitive science and neurology. De Jaegher [2013] deploys an embodied model to explore a more integrative model of autism which does not position the autistic individual as the unitary location of autism:

“Sense-making plays out and happens through the embodiment and situatedness of the cognitive agent: her ways of moving and perceiving, her affect and emotions, and the context in which she finds herself, all determine the significance she gives to the world, and this significance in turn influences how she moves, perceives, emotes, and is situated […] I suggest that social interaction difficulties are not to be considered exclusively as individually based, but that the patterns in the interaction processes that autistic people engage in play an important role in them.”

In other words, autistic consciousness is embodied in a sensory and social, material world. It’s a way of experiencing and interacting with the world which, in turn, creates an ‘identity’ in the world as an autistic person.

Foucault’s more discursive approach:

“… aims to reveal the contingent and historical conditions of existence. Thus he not only provides quite a shift from earlier discourses on the self, but also adds notions of disciplinarity, governmentality, freedom and ethics, corporeality, politics and power, and the historico-social context.” [Besley, 2003]

This shifts discussion of autistic identity on its axis. Neurodiversity was first popularised by Judy Singer in the late 90s and took off through the internet spawning a human rights movement. For the first time autism began to be placed in historical context as an identity contesting the imposition of the dominant psychological model of autism – although previous psychological models still continue to structure much of the neurodiversity discourse. Autism as an identity can be shown to enhance quality of life for autistic people [Lamash, 2024] but it can also become prescriptive if it fails to locate autism in the world and insists on locating it in the minds of autistic people as per its origins in pathologising psychology. What if, on the other hand, autism really is located in interactions between autistic subjectivity and the material world? What if autistic people have bumbled along for millennia in villages and towns and cities doing the kind of labour that just doesn’t involve modern constructs such as ‘ability to work in a team’ or Myers-Briggs profiles. What if everyone just worked around people they experienced as ‘awkward’ or ‘eccentric’. What if autistic people often lived precariously around the margins, perhaps often ended up in gaol (as urban working class autistic people still often do). What if our neurotype just wasn’t that big of a deal before post-industrial societies developed advanced ‘technologies of the self’ – or Foucault’s ‘panopticon’ of social control through surveillance and conformity. I once asked my mother why people in rural villages tended to be so eccentric: “Because no-one’s watching you, darling”.

If we situate the rise and rise of autism in history rather than in medical/ecological conspiracy or nature, we take notions such as ‘double empathy’ out of sociology and into a critique of post-post-industrial capital and its techniques of social and economic discipline. We start to question why a highly extractive economic system can’t accommodate and use our skills, why institutional systems are now such an inflexible conveyor belt through a sensory hell we’re unable to cope with them, why failing to conform to the rigid disciplines of the ever-proliferating niche identities that consumer capitalism seeks to exploit is now so unacceptable that it needs to be diagnosed as aberrant and treated? Why do I have to endure melt-down due to the pulverising sensory overload of commercialised modern airports unless I use assistive tech and a lanyard identifying me as cognitively defective? 40 years ago I could stroll through an airport unassisted as calm as a cucumber. Now I need assistive tech just to deal with a supermarket. Why do I need the legal protection of ‘reasonable adjustments’ to cope with an open plan office calculated to allot the least measurable space per human in a noisy sick building so that colleagues just can’t help breaching my sensory tolerance?

To me, the really compelling question is how on earth do NTs cope with all this? Badly, apparently, since a record number of them are signed off long-term sick or doggedly resisting being rounded up from working at home. So badly that a centre-left government seeks to justify cuts to the most vulnerable deployed to manage an economically unsustainable tsunami of inability or unwillingness to cope with the daily assault on reason and perpetual manufactured anxiety to the sole benefit of an increasingly oligarchic corporate state capture? Rather than hoping the Chancellor will find some change down the back of the sofa, shouldn’t we be fielding a rather more structural critique with rather more vim?

So what to make of identity and masking in an embodied and historically situated model? If autism as a modern construct is a product of history (not simply a description of a neurological type which has always existed), shouldn’t we be demanding recognition that post-industrial technologies of social control and economic extraction are the problem rather than individualising autistic subjectivities as problematic within a neoliberal regime that wants to standardise us as oven-ready employees rather than accommodate us (or anyone else)? Shouldn’t we be pointing up the essentialising of gender stereotypes in the way that masking in female autism is being modelled and recognise that gender is a neurotypical technique for social control rather than a phenomenon located within the mind? That male autistic identity is less of a ‘problem’ because its stereotype happens to match the current psychological model of autism? Shouldn’t we be treating masking not as a compensatory strategy for our shortcomings but the survival response of an oppressed class of people to an unreasonable regime of punitive discipline, surveillance and conformity tailored to the requirements of post-industrial financialised capitalism’s insane rate of extraction of value from pretty much every worker? Perhaps it’s time to organise around the specificities of neurodivergence through which we’ve already achieved a great deal, but coordinate actively with anyone and everyone else organising for social and economic conditions fit for human beings. Shouldn’t we be demanding a better world for everyone?

-o0o-

Sources consulted:

Baron-Cohen,S & A M Leslie, U Frith [1985] “Does the autistic child have a “theory of mind“?, Cognition, Oct;21(1):37-46. doi: 10.1016/0010-0277(85)90022-8.

Besley, Tina [2023] “Heidegger and Foucault: Truth-telling and Technologies of the Self’, Access: Contemporary Issues in Education, VOL. 22, NO. 1 & 2, 88–98 https://pesaagora.com/access-archive-files/ACCESSAV22N1N2_088.pdf

Echols, Alice [1983] “Cultural Feminism: Feminist Capitalism and the Anti-Pornography Movement”, Social Text, No. 7 (Spring – Summer, 1983), pp. 34-53 (20 pages). Published By: Duke University Press

De Jaegher, Hanne [2013] “Embodiment and sense-making in autism”, Frontiers in Integrative Neuroscience, Vol 7, 26 March | https://doi.org/10.3389/fnint.2013.00015

Echols, Alice [1983] “Cultural Feminism: Feminist Capitalism and the Anti-Pornography Movement”, Social Text, No. 7 (Spring – Summer, 1983), pp. 34-53 (20 pages). Published By: Duke University Press

Huggins, C. F., Donnan, G., Cameron, I. M., & Williams, J. H. [2020] “Emotional self-awareness in autism: A meta-analysis of group differences and developmental effects.” Autism, 25(2), 307-321. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361320964306 (Original work published 2021)

Kay, J. B. (2024). The reactionary turn in popular feminism. Feminist Media Studies, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/14680777.2024.2393187

Foucault, Michel [1988] Technologies of the Self, Amherst : University of Massachusetts Press, internetarchivebooks; printdisabled

Lamash, Liron, et al [2024] “Autism identity in young adults and the relationships with participation, quality of life, and well-being”, Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, Volume 111, March 2024, 102311

Milton, D. (2012) On the Ontological Status of Autism: the ‘Double Empathy Problem’. Disability and Society. Vol. 27(6): 883-887. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2012.710008

Urbanski, Steve [2011] “The Identity Game: Michel Foucault’s Discourse-Mediated Identity as an Effective Tool for Achieving a Narrative-Based Ethic”, The Open Ethics Journal, 2011, 5, 3-9

Weir, Elizabeth et al [2021] “The sexual health, orientation, and activity of autistic adolescents and adults”, Open Access: Autism Research https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/aur.2604